How Green is the Riff?

It's amazing who you meet when you go travelling, especially in places like the Rif mountains.

It's amazing who you meet when you go travelling, especially in places like the Rif mountains.

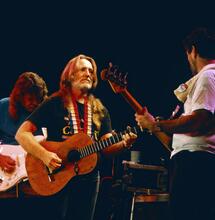

It's amazing who you meet when you go travelling, especially in places like the Rif mountains. We were over there researching the political and economic issues of bif in the Rif but that sort of work can get a bit stressful sometimes so plenty of hammock time is called for... Mmmm, the Monkey Man's hardella, dobley zero zero - the best. Hot sunshine, forty-plus degrees. A gentle breeze and a lazy swing in the hammock. Before I knew it I was in slumber land. Then came an ear-splitting crash, a puff of smoke and a flash of light - was I dreaming? I rubbed my eyes. As the smoke started to clear I could see a man floating in front of me - he was sitting in the lotus position, hovering above a large, shiny metal chest. His grey hair was dragged back into a ponytail and his woolly beard gave him the look of an old colonial explorer. He was dressed in a pale blue Pakistani dress suit, his eyes were twinkling and he was smiling a mischievous smile... This is Malcolm.

Malcolm McEwen is a self-styled travelling soil scientist and Sufi mystic with a degree in Habitat and Soil Management. He has a dedicated and adoring following as Youtube's King of Compost but now he spends most of his time conducting research and consulting with farmers in Africa and south Asia. He's been leading this nomadic lifestyle for the last seven years with his mission being to help farmers adopt better practices and resource management techniques. He has also learnt a lot while he's been on the road. His website Persephone Habitat and Soil Management (www.phasm.co.uk) is a free resource and virtual consultancy for anyone wanting to develop sustainable agriculture. As we speak, Malcolm is busy researching the implications and opportunities of cannabis agriculture in northern Morocco; he's got some very interesting points to make so SSUK took advantage of our meeting and conducted the following interview...

SSUK: Before we start talking about cannabis agriculture in the Rif mountains can you give us an idea of the broader issues you deal with?

Malcolm: Yes, of course. Since the advent of the ‘Green Revolution' agriculture has become increasingly dependent on mechanization and the industrial scale use of artificial manures, pesticides and herbicides. Once heralded as the end of food shortages, these modern practices have since lead to accelerated soil erosion, water pollution, a frightening loss of biodiversity and pervasive habitat destruction.

There have been a good deal of social implications as well; men who used to drive horses have been replaced by satellite-controlled tractors pulling disc harrows. Whilst this may have led to greater efficiency in short-term production it has also created unemployment and precipitated the demise of rural communities. So, whilst the ‘Green Revolution' might have theoretically put more food on the plate it did so at the cost of the environment and the rural social systems that depended upon it; a cost we now know to be unsustainable.

SSUK: Can you take us a little bit deeper with regards to the chemical side of things?

Malcolm: Sure. Monoculture farming has become a generator of ‘green deserts', vast fields devoid of anything except a single strain of plant. Absurdly, in the name of efficiency some of these green deserts stretch to the horizon and beyond; they are maintained by regular applications of oil-based fertilisers, herbicides and pesticides. The GPS-controlled tractors trace and retrace their previous tracks through these green deserts whilst they spray the crops with all these noxious agri-chemicals. Under the industrial scale farming system there is no room for biodiversity so the system needs these apocalypse-inducing chemicals to maintain production levels.

Most agricultural crops, particularly grasses and cereals, require 250kg of nitrogen to be added per hectare per year. This nitrogen is produced by ‘fixing' atmospheric nitrogen - a process that requires lots of energy, which is why most nitrogen fertiliser factories are located very close to oil refineries. This form of nitrogen is highly soluble so, whilst effective in plant nutrition, it is easily leached from the soil into water sources where it causes pollution. Furthermore, it interferes with the carbon cycle, accelerating CO2 evolution and eroding the soil's organic reserves.

The loss of Soil Organic Carbon through both cultivation and fertiliser use is believed to be a major contributor to the current elevated CO2 levels in the atmosphere with as much as a third having originated directly from agriculture.

The use of herbicides and pesticides have similarly had major implications by causing massive declines in common herbs, insect populations, small mammals and birds that depend on them. This is by no means a recent phenomenon - we have known about the ill effects of pesticide use since 1960 when Rachel Carson got Silent Spring published. Now more than fifty years have gone by yet most of the bread you eat will have at least one herbicide and one pesticide application whilst in the field; if you are wearing cotton then this has had at least two more, and if you're a smoker it is highly likely that your tobacco still contains traces of the pesticides used in production.

SSUK: That's some scary stuff. How does it all relate to the cannabis agriculture of the Rif?

Malcolm: When we look at the Rif mountain agriculture we see little evidence of the above practices. The mountains are entirely unsuitable for mechanization and they are still tilled by hand and/or with a single plough pulled by a donkey or a couple of horses. It is hard, crude and poorly paid work. It is only performed once to prepare the ground for sowing and it is also the principle means of controlling [unwanted] weeds: no herbicides are or could be used here.

Also, dotted in and amongst the cultivated fields are various fig trees which, under the hot summer sun, produce giant, soft, sweet fruits in shades of green, pink and yellow. Such is the abundance of these fig trees that their essential symbiotic partner, the fig wasp, is in similar abundance - this would not be the case if pesticides were in use.

Relative to a lot of modern agriculture the cannabis agriculture in the Rif is surprisingly eco-friendly; with no herbicides or pesticides in use the spring time is awash with floral colour and the air is buzzing with bees and other pollinators. Summer time is equally as active with swifts performing their acrobatics as they scoop the dusk flies out of the air and 40 watt light bulbs become a Mecca for successive waves of moths. These winged evening visitors may be a nuisance to some but they are the adult stage of the insect and to the ecologist they are evidence that the environment is providing sufficient food for the grubs and caterpillars they originate from.

SSUK: How about fertilisers? There has been a bit of worry in recent years that Riffian farmers are starting to use chemical fertilisers on their crops.

Malcolm: When it comes to fertiliser use, the Riffian agronomists add no nitrogenous fertilisers but they do use ammonium phosphate which contains nitrogen. Ammonium phosphate is a chief product of Morocco and it is also, arguably, an unnecessary application. What they use more of is animal manures - mainly from sheep, cattle and horses. This is applied fresh and directly to the land at the same time as it is cultivated and sown. The Riffians are missing a bit of a trick here though; because their manure is not composted properly they are only harnessing around 10-15 per cent of it's potential nutritional value - with proper composting they could boost that to 80 or 90 per cent.

SSUK: It sounds like the agriculture in the Rif is quite sustainable - is that true?

Malcolm: Well, all agriculture is environmentally damaging in some respects but, compared to most other agricultural choices, cannabis is a very ecologically sustainable crop. I understand that cannabis has been grown in these mountains for between three and four hundred years - this has sustained the local human communities for all that time and the sustenance of that, through the generation of employment, filters it's way throughout Moroccan society.

More recently though, the cannabis industry in the Rif has grown to international proportions in order to supply the demand in Europe and elsewhere. Despite this, it's impact on the local environment has been minimal and with a little planning and consideration the industry could turn itself into an example of excellence in agriculture.

This is all in stark contrast with the impacts of commercially cultivated indoor cannabis which is the other chief source of Europe's cannabis. Done on an industrial scale, this indoor method destroys good housing, uses large amounts of electricity and produces a far more potent end result. Such an industry contributes nothing to either the society in which it is based nor to the environment in which it operates. This is in comparison to the Rif, where cannabis cultivation and production is a family affair - the backbone of the community; it sustains farmers, the land, tourism and the community as a whole.

There's also another important point I want to make about the cannabis crop in the Rif; as it is grown principally for the resin glands produced by the female flowers, the majority of the plant, the biomass, is not exported. The extraction of the resin is achieved by physically beating the flowers over a fine mesh to dislodge and collect the glands. The husk, the stalks and large amounts of the beaten flowers are then returned to the land from which they came - this means they are, effectively, growing a green manure! In terms of chemical composition, the resin is quite innocuous; it contains no proteins, carbohydrates or nutritional value and is made of little more than water and air (carbon, hydrogen and oxygen). All this means that hashish exports do not rob the ground of fertility as only a very small percentage of the biomass is being exported.

SSUK: That's fascinating stuff. I know you've thought about cannabis cultivation and it's role in the wider world - could you tell us a bit about that?

Malcolm: Yes, we have to ask ourselves the question as to what extent does hashish production contribute to the global objective of sequestering atmospheric carbon and could/does this industry contribute towards a zero-carbon society? The answer to this is relatively easy to calculate; as is tailoring cannabis production to encourage nutrient accumulation, building fertility at the local scale. Both of these objectives are complimentary - we could build fertility and achieve the global objective of carbon sequestration without compromising crop yield or quality. Arguably, a cannabis industry that is sustainable, environmentally friendly and socially responsible is, regardless of your political views, far better than one that is not. And lets face it, as long as there are people on this earth there will always be a cannabis industry to supply them.

So there you have it folks. With a little care and intellectual investment the hashish industry of Morocco can be turned into a positive force for the environment and society in general. When analysed in contrast to the impact of indoor hydroponic cultivation, these very simple arguments alone should be more than sufficient to persuade policy makers to rethink their ignorant and highly politicised laws regarding cannabis. You've got the arguments, now it's your job to start informing the policy makers!

Streamers>>>

The mountains are entirely unsuitable for mechanization and they are still tilled by hand

the cannabis agriculture in the Rif is surprisingly eco-friendly; with no herbicides or pesticides in use

compared to most other agricultural choices, cannabis is a very ecologically sustainable crop

with a little planning and consideration the industry could turn itself into an example of excellence in agriculture.

hashish exports do not rob the ground of fertility as only a very small percentage of the biomass is being exported

a cannabis industry that is sustainable, environmentally friendly and socially responsible is, regardless of your political views, far better than one that is not